The Levellers: rebels with a cause

Depending on the context, to ‘level’ something means to either raze it to the ground or bring it to the same standard as something else. To Cromwell and conservative Parliamentarians, the name they unlovingly bestowed onto the radical political group that emerged after the first English Civil War followed the former meaning. To them, their ambitions were unfeasible, dangerous and destabilising. They would only bring with them, in Cromwell’s words, “the reducing of all to an equality.”

The Levellers, however, would much prefer the latter definition if they had to go by the name given to them. Suffrage for all, reform to law in the service of equality and the abolishment of monarchy. Surely these were principles that would raise all to the same denominator. So the Levellers thought, and so Cromwell dismissed. In a time of political upheaval, they dared to upheave a little more than what could be tolerated.

The levelling of the first English civil war

The Levellers had arrived at a time which would perhaps provide more leniency to their ideas than in the past. The first English Civil War began in 1642 and created a bloody schism between Parliament and the monarch. Ultimately, the war closed with a parliamentary victory and the capture of Charles I by the Scots after the Battle of Naseby in 1646. The wound it left, however, was still raw and deep. The country, by the time of the Levellers’ formation, was in turmoil following the war that had claimed 5% of its population in just four years.

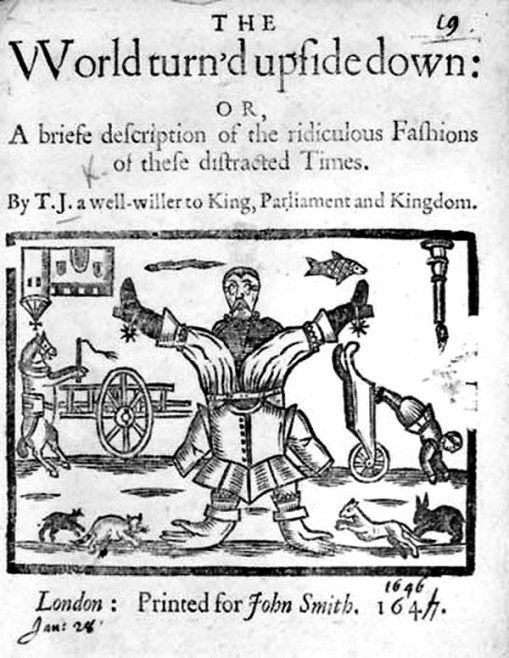

“The best estimate of the civil war says it was proportionally more destructive of life than the First World War,” says Fiona McCall, PhD in seventeenth- and sixteenth-century social history and lecturer at the University of Portsmouth. “You might have had your house destroyed or blown up. People are killed; civilians are killed. The classic pamphlet of that time would express that the world has turned upside down.”

The country was indeed upside down, but the class system was oriented the same. The monarchy may have been neutralised, yet political authority remained concentrated among the same social strata. Members of Parliament were overwhelmingly drawn from the gentry and aristocracy. Voting rights were tied to land ownership, excluding the majority of adult men from meaningful political participation; women were excluded entirely. Landless labourers, tenant farmers, and wage workers – who formed most of the population – had no formal voice in the system that governed them.

The contradictions were apparent for many of the men who had fought in the New Model Army. The Parliamentarian victory depended on an army composed largely of commoners. Following it, these commoners garrisoned towns, suppressed royalist uprisings, and maintained public order. Ultimately, though, despite their crucial role during and after the war, they were not legally entitled to suffrage unless they owned land.

What compounded this grievance was Parliament’s refusal to pay them. Over £3 million was owed to infantry and cavalry for salary in arrears. Resentment within the military formed a hotbed, and from this hotbed grew radical political sentiment.

“Their fundamental thought was: ‘We’ve won this war. We peasants and labourers have beaten the King. That’s a sign of God’s favour,’” says Warwick George, PhD in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century Church History. He continues: “‘Surely He would want us to enjoy the benefits of equal citizenship as well as the rich.’”

With this philosophy emerged the Levellers as a political force.

An Agreement of the People, a disagreement in debate

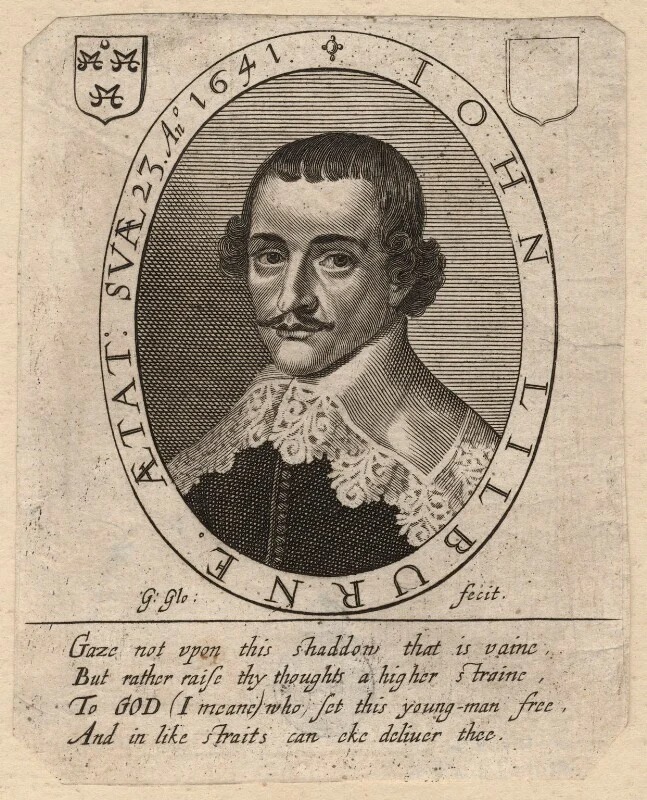

Pamphleteers John Lilburne and Richard Overton, both repeatedly imprisoned for their advocacy, quickly became the Levellers' most recognisable figures. From the Tower of London in 1646, Lilburne published England’s Birthright Justified, arguing that “freeborn” rights inherent to all meant that the government could only rule under popular consent. Overton assisted in clandestine printing and reinforced Lilburne’s sentiments with published works such as An Arrow Against All Tyrants.

Within the army, figures like Colonel Thomas Rainsborough helped disseminate Leveller ideas among soldiers. Underlying sentiment amongst the military, with the aid of leadership, had turned into a cohesive political ideology.

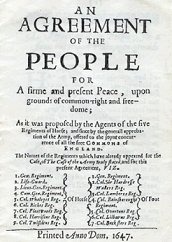

By 1647, this ideology was composed into a manifesto: An Agreement of the People. Presented to Parliament and debated at Putney Church, Leveller representatives proposed their vision to army grandees and conservative parliamentarians, including Oliver Cromwell. Here, they argued for popular sovereignty against suffrage via property ownership. The Leveller consensus was distilled by Rainsborough’s declaration during the debate: “I think that the poorest he that is in England hath a right to live as the greatest he.”

To Cromwell and his allies, though, such proposals were dangerously destabilising. Near-universal suffrage threatened to dissolve the social order that Parliament relied upon to govern. Total right to votership to the populace could collapse the current government, one which was relied upon to retain some stability with a monarch incapacitated. The debate at Putney dragged on through the autumn until Charles I escaped captivity, inciting Cromwell to execute him in 1648. He and the Levellers were in agreement over that, at least.

Their remaining demands were nevertheless intolerable. Radicalism was spreading through the army, and some soldiers had mutinied. Mutiny could incite yet another civil war if left unchecked. In May 1649, Cromwell and his peers acted decisively, suppressing Leveller-influenced mutineers at Burford. Hundreds were imprisoned; three of their leaders were executed. Lilburne and Overton were arrested again and tried for treason.

“By the 1650s, the Levellers had been stamped down by Cromwell, and property rights were firmly reasserted as the basis for suffrage,” McCall notes.

A plausible vision for the future, a suppressed one under Cromwell

All of this resulted in the term “leveller” being defined as what Cromwell and his ilk saw it to mean - a mere descriptor of a group of rebels who wished to create further destruction to a Britain in ruins. However, whilst their influence had perished by the time Cromwell was anointed Lord Protector, their ideas have been resurrected throughout British history with more success. In 1918, all men were given the right to vote, regardless of property ownership or income. In 1928, women received full suffrage. “Our modern political distinctions can all be traced back to this era,” confirms George.

Whilst the Levellers' ideas were thought radical in their time, they have since been revised and now form the basis of British society. In many ways, history has proven them faithful in their mission to level - in the more admirable definition of the term.

Post a comment