Adaptation: Being Charlie Kaufman

When walking the dangerous tightrope that is absurdist writing, it is hard to imagine Kaufman unconscious of the abyss of insincerity, pretension and nonsense that stretched below him when choosing to abandon writing Adaptation as a humble retelling of a book about flowers.

What he gave the studio was instead a screenplay about himself during the painstaking process of writing the film.

Committed to an ambitious retelling, though, Kaufman took a leap of faith by submitting the screenplay. A leap of faith he thought “was ending his career”.

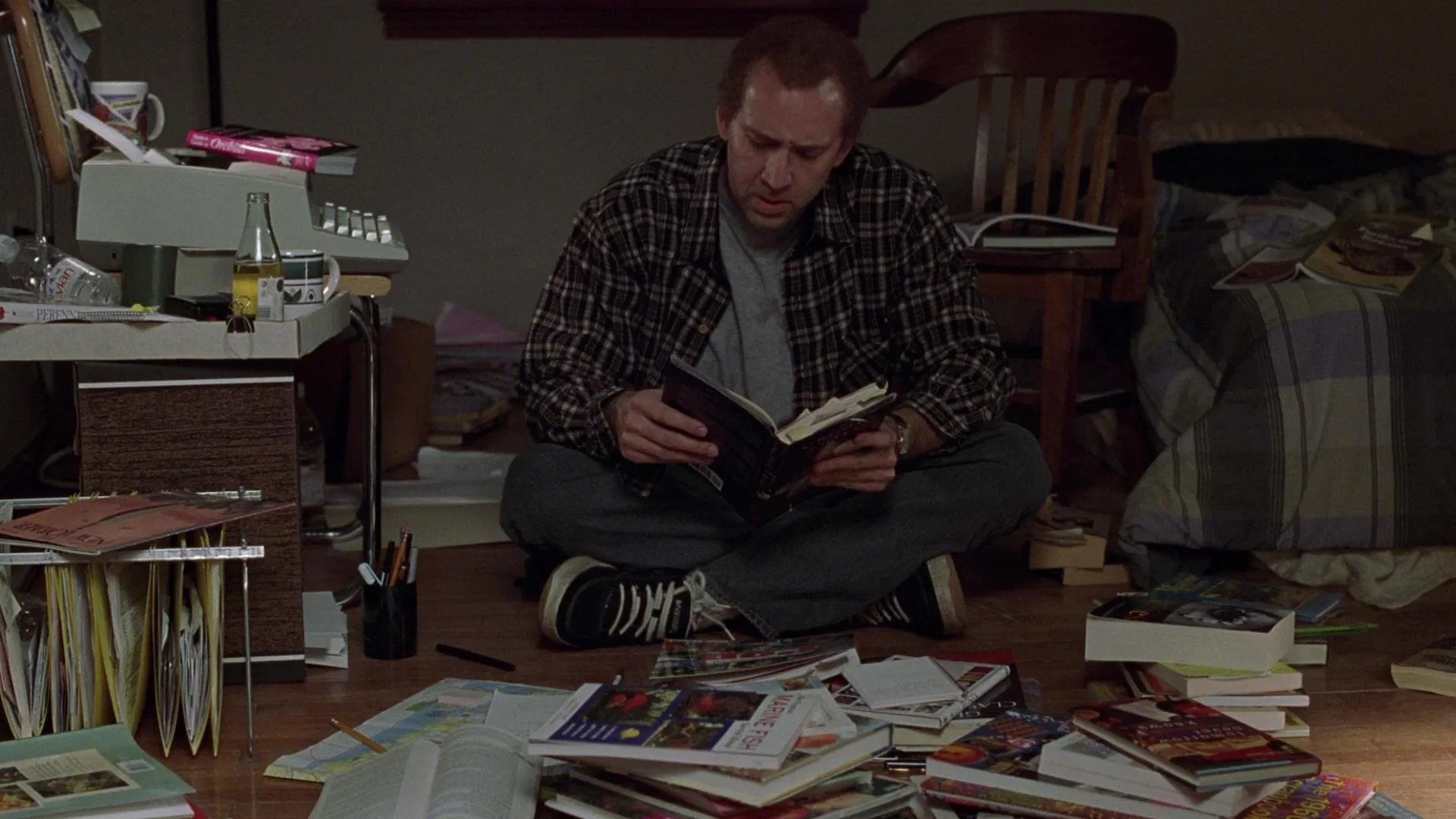

“To see the world through a grain of sand and heaven through a wildflower”, as William Blake said, is something Kaufman – both within the film as its protagonist, Charlie, and without – seeks to write in advocacy of beauty in nothing, yet finds nothing beautiful. Sweat beads off his balding forehead as he pours their feverish droplets over a screenplay that, it is clear, he cannot bring to fruition.

Like Camus’ absurd Sisyphus, Charlie, for most of the film, is pushing a boulder uphill, only for it to roll back down for him to courier it again to an unreachable destination.

Albeit, Adaptation, in signature Kaufman style, doesn’t tread on an altogether melancholic premise with heavy feet. Instead, the film enthusiastically dances into introspective sardonicism. Kaufman indulges his ego by placing himself as the film’s figurehead whilst simultaneously keelhauling it throughout the film. An altogether pathetic caricature of him is played by Nicholas Cage with verisimilitude that makes the character’s misanthropy sympathetic as well as incessantly funny.

Even more impressive of a performance it is for Cage as he flips between the self-loathing Charlie to his infallibly spirited twin, Donald. Whilst he portrays Charles as a reluctant Sisyphus, Cage, endorsed by Kaufman’s writing, plays Donald as his philosophical opposite. The crux of Camus’ philosophy is essentially etched into the fibre of Charlie's counterpart; “one must imagine Sisyphus happy”.

Past the wit and absurdity, the film holds sincere to the narrative of Charlie Kaufman ameliorating himself, as mirrored by his fictitious twin brother. If Sisyphus was doomed to his fate by Zeus, he must have had a twin brother. But, if there were heaven to be found in such a purgatory, Donald would have found it.

The realisation by Charlie, tutee as both protagonist and screenwriter to the entirely fictitious Donald, is that beauty can be found in the journey up the hill, not in its destination. This is a thread weaved in his latter works like Eternal Sunshine and Synecdoche, New York, but arguably began to be spun here.

What Kaufman bares to the audience at the end of his run on the metafictional tightrope are two brothers who share the same flesh, yet their souls lie entirely separately in the mind of their writer. Charlie is Sisyphus at the beginning of the film, and so is Donald, but only one can imagine himself happy. The journey towards both finding it is the journey of Kaufman as he had written them. To this end, he walks the tightrope well.

Post a comment